I am on vacation in Chile and exploring various techniques for recording sounds around me. I do some outdoor recordings but try to focus on indoor environments because of my ongoing AMBIENT project. In this blog post, I reflect on how challenging it has been.

Annual projects

The recordings are part of my annual sonic rhythm project, which is my third annual project.

In 2022, I recorded one sound action per day. That was with a very simple setup: my mobile phone and a Røde VideoMic Me-C, a directional microphone that can be plugged into a mobile phone through a USB-C connection. The simple setup was probably the reason, I succeeded in carrying out that project.

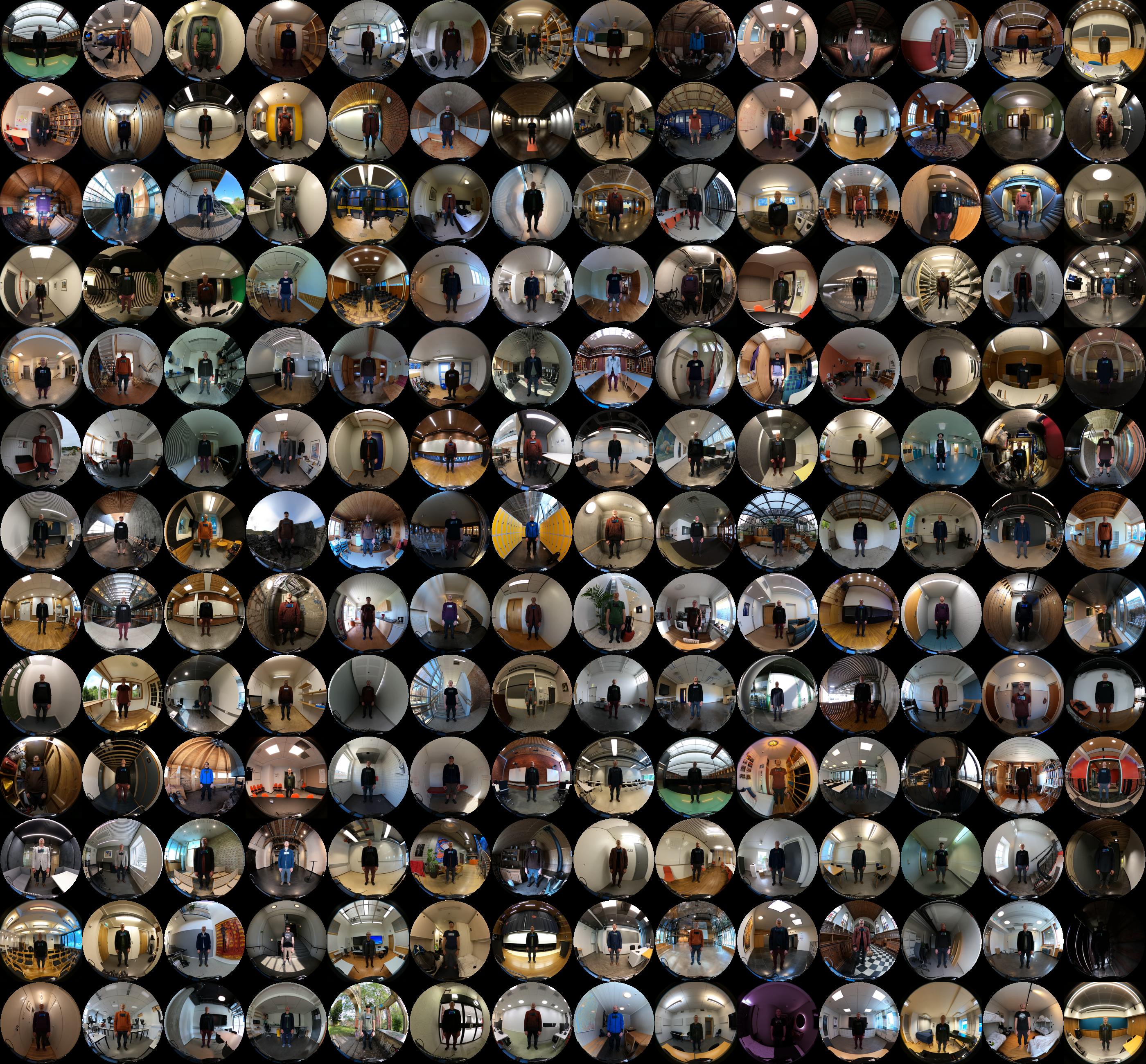

In 2023, I was more ambitious and embarked on a journey of standing still ten minutes daily. I recorded my (micro)motion with my mobile phone hanging on my chest and also captured both 360 video and ambisonics audio using a GoPro Max and a Zoom H3 recorder. It was challenging to do it every day, but I managed. That was probably because the main focus was on standing still, with the audio and video recordings being a add-on task.

Capturing sonic rhythms has been the most difficult so far because I am trying to capture something that is neither clearly in the foreground nor the background.

Foreground and background

In the visual domain, one often talks about foreground and background elements. In a portrait, the face is in the foreground. In a photo, it is sharp and well-lit and, therefore, stands out from the background. On the other hand, the background is typically blurred, giving a sense of where, what, and when, but not much more.

The same can be said about audio. We typically record voices or instruments in the foreground, while trying to eliminate background noise. Wanted background sound includes reverberation, giving a sense of location. Unwanted background sounds include traffic noise, people talking, etc. Sometimes, the background is wanted. For example, radio reporters often stand in a busy street to give a sense of “liveness” to their reports.

Even though it wasn’t conceived as such from the beginning, I now realize that my two previous annual projects have focused on foreground and background sounds, respectively. The Sound Actions project focused solely on foreground elements, things I (or others) did.

Most of the recordings were short, and, in most cases, it was relatively easy to record them. After all, since they were based on doing something, I could adjust the time (and usually location) of when I wanted to do the recording. Sometimes, I repeated the action a few times to get a better recording. Other times, I had to isolate myself and the action from neighboring sounds to create a good recording. Having a directional microphone helped isolate the action, although it sometimes captured some background elements as well.

My StillStanding recordings were quite different. The main focus was on finding a location where I could stand uninterrupted for ten minutes. In many cases, I stood in rooms without other people; hence, there were also few foreground sounds in the space. In some cases, I stood in lively spaces, but the chatter of people, traffic noise, or animal sounds typically formed a background texture.

Thus, the StillStanding sound database mostly contains background elements.

Foregrounding the background

It has taken me some time to understand why the SonicRhythm project has become more challenging than the two previous projects. Now, I realize it is because I am trying to “foreground” a background sound. This is more challenging practically, conceptually, and technically.

First, finding continuous, repetitive sound sources is more challenging than anticipated. I still need to formulate a good theory about sonic rhythms, but I was thinking about continuous, repetitive sounds. I started thinking about this when standing still last year. Often, I thought about sounds in space that had a rhythmic character. Often, fans of different types: fridges, ventilation systems, PCs, etc. That is also what I have ended up recording the most of. But there are also rhythmic elements in car traffic and windows blowing in the wind. Looking back at what I have recorded, I find fewer natural sounds than anticipated. That is also because one of the project’s requirements has been to record indoor environments. This can include outdoor sounds as long as they are recorded indoors.

One interesting aspect that I will explore in future recordings (and analysis), is the difference between clearly audible rhythms and various types of noise. When does noise become rhythmic, and when does a rhythm become noise? This is partly a perceptual (and psychoacoustic) question, but it is also aesthetic.

I look forward to delving into that type of analysis in the future.