I have been challenged to talk about innovation in the light of Open Research today. This blog post is a write-up of some ideas as I prepare my slides. Looking at my blog, I have only written about innovation once in the past, in connection to a presentation in Brussels about Open Innovation. Then, I highlighted how my fundamental music research led to developing a medical tool. That is an example of “classic” innovation, developing software that solves a problem. However, as I will explore in this blog post, innovation can be broader than that.

Innovation

What is innovation? The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) defines innovation as:

a new or changed entity realizing or redistributing value".

Wikipedia goes on to explain this as

the practical implementation of ideas that result in the introduction of new goods or services or improvement in offering goods or services.

I like that they include “services” here as an addition to “goods”. That opens for including various types of humanities-oriented innovations, including cultural and social innovation.

While looking at various definitions, I found that the Merriam-Webster Dictionary discusses the difference between innovation and invention:

the first telephone was an invention, the first cellular telephone either an invention or an innovation, and the first smartphone an innovation.

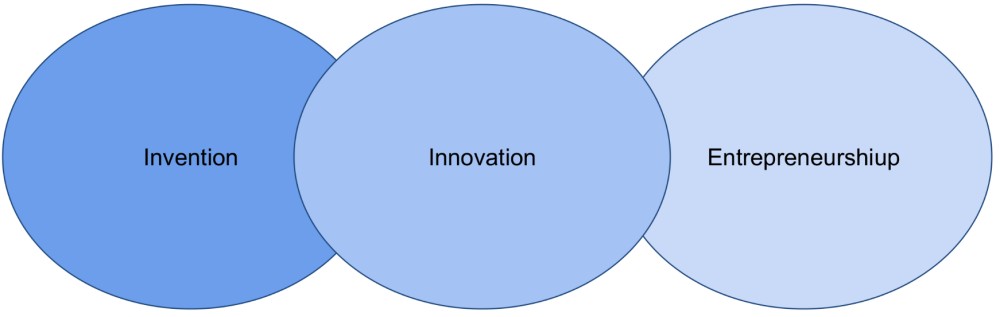

This distinction is helpful. An invention is more of a paradigm shift, while innovation can be the gradual improvement of the original invention. One could argue that research is all about invention and innovation. After all, researchers aim to develop new ideas, solutions, tools, etc. Researchers are good at creating inventions but do not necessarily focus on innovation per se. That said, incremental research (which much research arguably is) could be seen as a form of innovation.

The University of Oslo defines innovation as knowledge in use. It focuses on research as the basis for new solutions to important societal needs:

By promoting innovation and entrepreneurship, UiO ensures that our research can be transformed into solutions that have significant value for the society.

That is an instrumental way of looking at the problem, I think, moving from invention (which could include basic research results) to innovation (putting the knowledge to use) and entrepreneurship (creating economic value). In my presentation, I showed the relationship between the terms with this figure:

Fostering innovation through Open Research

The starting point for my invitation to the seminar was my advocacy for Open Research. Readers of this blog know that I frequently argue that embracing openness in all stages will lead to better research.

I was somewhat puzzled when asked to discuss the conflict between Open Research and Innovation. There may be some people who feel that there is a disconnect between the two. However, I think that Open Research could be a driver of Open Innovation.

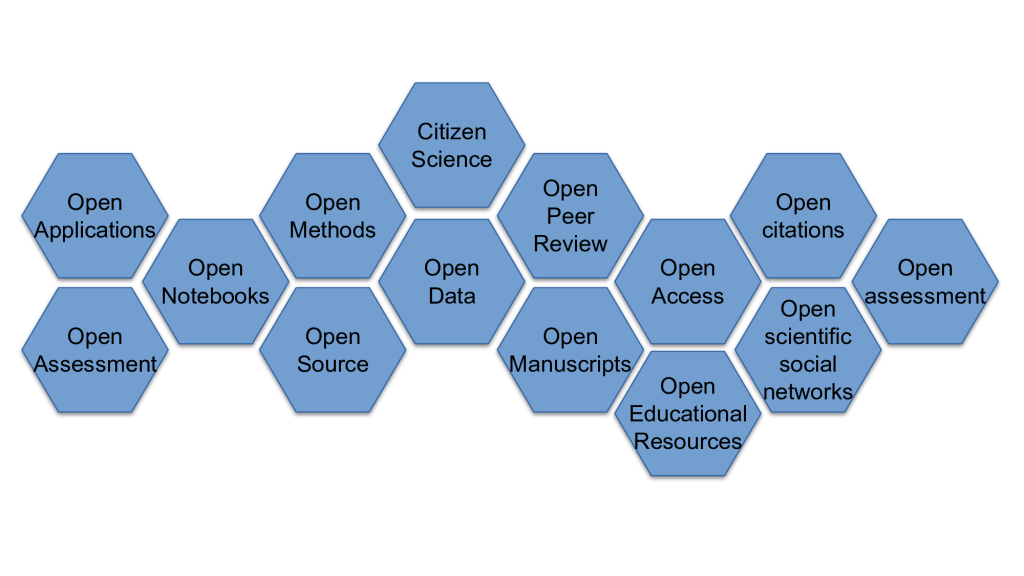

What is Open Innovation, then? When talking about Open Research, I often present the “puzzle image” I made some years ago (which, of course, is openly available):

I argue that innovation builds on sharing and learning (or learning and sharing). Either way, as research builds on research (we all stand on the “shoulders of giants”), innovation builds on innovation. It helps the innovation process if people can access past innovations (and inventions!). Making source code available helps others read, use, and develop it. Sharing data allows for more analysis and better services based on the data. Opening lab notebooks, methods reports, manuscripts, etc., allows more people to build on others’ work rather than inventing the wheel themselves.

Multi-disciplinarity as a driver of innovation

Innovation often happens when random people with different backgrounds work together. Some of my innovative contributions have come by suggesting solutions to fields far from my own, such as CIMA and some of our ongoing life science projects (ABINO, ITOM, AUTORHYTHM). Similarly, I highly welcome the contributions from other disciplines in my own projects, such as MICRO and AMBIENT.

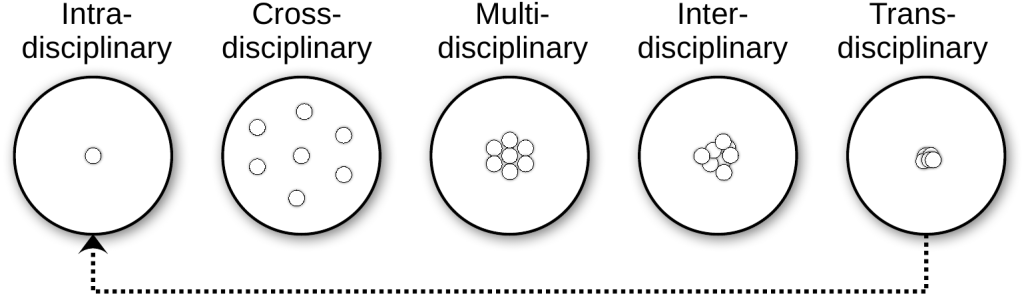

While some would call them interdisciplinary projects, I refer to them as primarily multidisciplinary. I have several times written about different types of disciplinarities on this blog. I often like to illustrate these differences with this figure:

There is no right or wrong here. Many people talk about interdisciplinarity, but most projects that reach out of a discipline would be cross- or multidisciplinary in my thinking. That is fine and may be more productive. In such situations, people have their disciplinary backgrounds and work with “others”. Defining the others as “others” indicates that they do not work inter- or transdisciplinary. The latter requires so tight integration of theories and methods that there are no “others” any longer.

Towards Open Innovation

There is much more that can be said about Open Innovation. As argued in today’s talk and this blog post, I encourage university leaders and funders who care about innovation to support multidisciplinary research projects that employ Open Research principles.