Today marks the 100th day of my annual #StillStanding project. In this blog post, I summarize some of my experiences so far.

Endurance

Some people questioned whether I would be able to stand still every single day for an entire year. But, hey, it is only ten minutes (out of 1440) per day, and even though my life as a centre director is busy, it is always possible to find time for a standstill sometime during the day.

As for time spent, I need around 20 minutes for the standstill itself; I spend a few minutes setting up and packing down. I often also spend a few minutes finding the room to stand in, so, all in all, I usually book a 30-minute slot in my calendar. I also spend some time transferring files, pre-processing the data, and running a quick analysis, which typically sums up around 30 minutes. Since this is not a particularly brain-intensive activity involving some minutes of waiting in between, I usually end up doing it (too) late at night, often in parallel to watching the news.

An hour per day is a considerable daily chunk, but carrying out the project as planned feels important. I do data collection for two projects, MICRO and AMBIENT, and the data will support two books (well, at least the Still Standing book that I am working on, but I also have plans for a book based on the AMBIENT project). The data is already source material for some students’ projects, and more will likely follow. I also hope some artistic work will come out of the data collection.

Throughout my #SoundActions project last year, I realized that doing something daily gives a project a lot of momentum. Last year I also spent something between 30 and 60 minutes daily on recording, processing, and publishing various environmental sound actions, which helped me focus on my research. When RITMO is “alive” during semesters, I typically have meetings most of the day, and I don’t have the luxury of countless hours doing research alone in my office. Sneaking in time for a 10-minute standstill helps me calm down in the middle of the day (think of it as a particular type of meditation) and spend an hour on my research daily.

If it weren’t for this project, I would not have spent that hour on other research activities; it would probably have been eaten up by random “important” things showing up. When I started my PhD fellowship, I remember my advisor, Rolf Inge Godøy, said that a dissertation is completed by writing 10 minutes each day. He was right; the many small steps make a whole. Now, my 10 minutes of standstill makes me spend at least 365 hours on data collection this year. That is not bad, I think!

Time and Place

In the beginning, the plan was to stand still around noon. It still is, and I have blocked out half an hour from 11:30-12:00 every day. However, I often have to move it to a different time slot in practice. My schedule is usually in flux as I try to adjust meetings and supervision with several people. Most days, I still do my standstill between 11:00 and 14:00, although there have been some exceptions. From conceptual and scientific points of view, it would have been best to stand still at the same time every day, but that wouldn’t have worked. One of the reasons I have managed to do 100 standstills in 100 days is that I have been pragmatic about the timing.

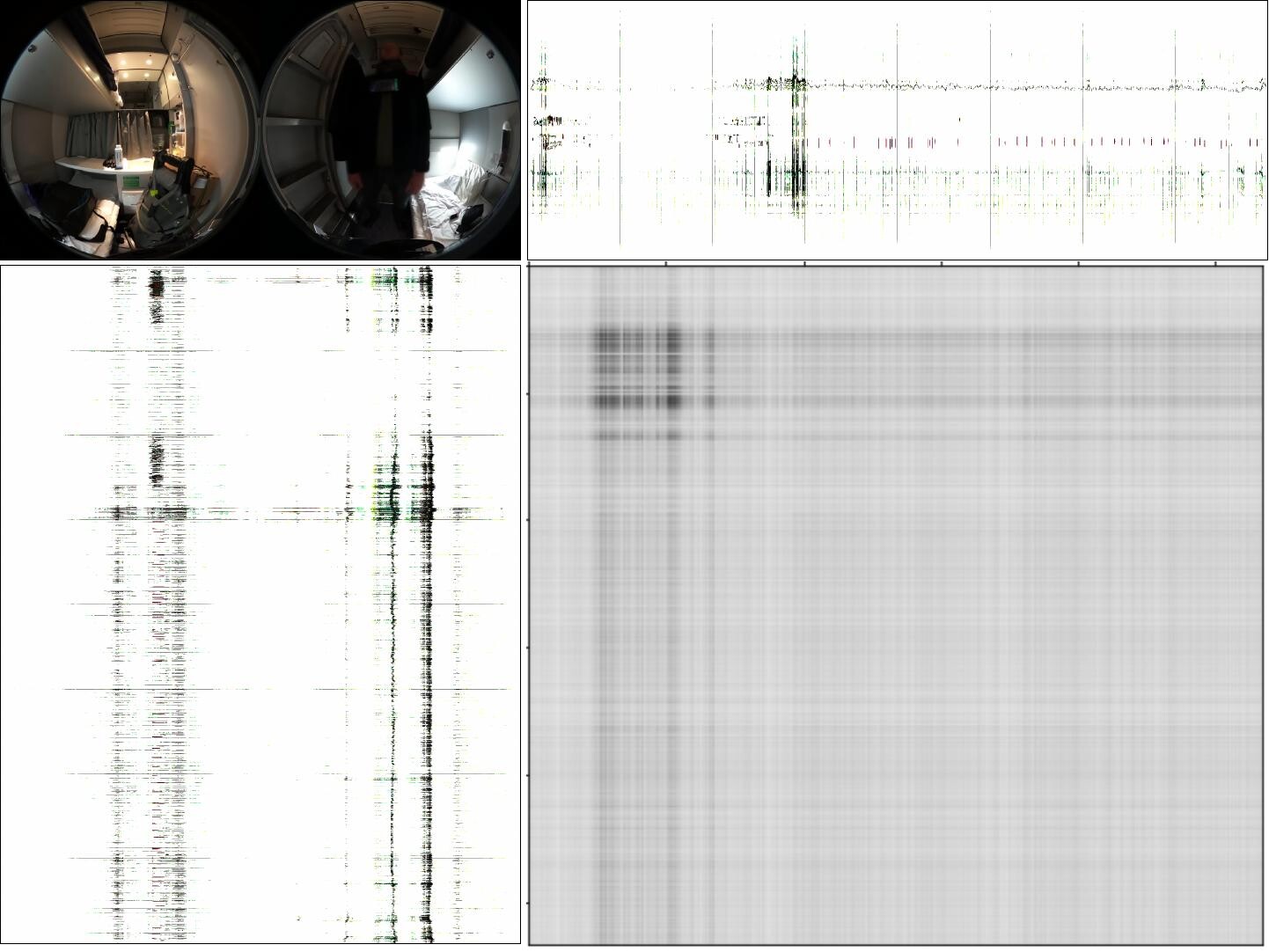

A few of my standstills have been deliberately out of schedule. For example, #StandStill 044 was done on the night train to Stavanger. I wanted to stand still on a train in motion and figured that the ride for the Bodies in Concert experiment was ideal since I would have my own train cabin. But that meant that I had to stand still at night. It was a memorable experience, though I am thrilled I made it.

It has been more challenging to find suitable locations. Remember that #StillStanding is focused on data collection for two projects. For MICRO and my Still Standing book project, it is the standstill that matters. Or, more precisely, the micromotion that I capture while standing still. The idea is to compare this longitudinal dataset with the other data in Oslo Standstill Database.

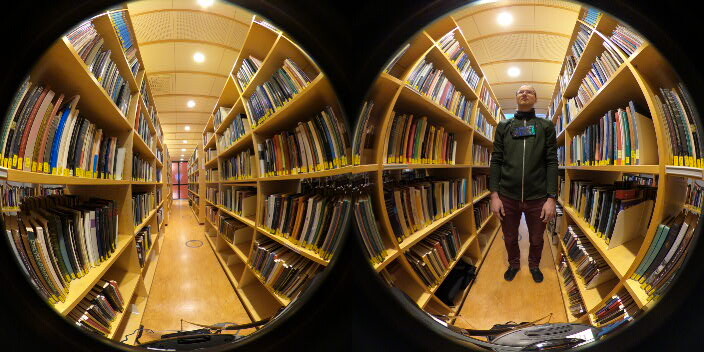

For the sake of the AMBIENT project, however, the focus is on the environment. That is why I stand still in a new indoor environment every day. This is easy when I am at UiO. There are thousands of rooms at the university, and, as a professor, I have access to many of them. Still, in the middle of the day, there are often people in the rooms, and I try to avoid places with people, both for privacy reasons and not to be disturbed. I started standing in various rooms at RITMO and have expanded to rooms in the Department of Psychology, located in the same building. When I attend meetings at the Department of Musicology, I find rooms in the ZEB building. But I need more rooms, so I will soon need to expand to other buildings on campus.

Weekends and vacations are more tricky. I have only so many rooms that I can use at home, and I want to save some rooms at home for when I am sick or unwell and cannot leave the house. So I have tried to be creative, including finding places in my neighbourhood that would work, such as #StandStill 092 when I explored the inside of a phone-booth-turned-library at Fagerborg in Oslo.

It has also been tricky to find places when I am doing some daylong outdoor activity, such as skiing. Sometimes I have done my standstill before leaving or after getting back, but I always carry my equipment around in case an opportunity arises. One such was the unexpected but exciting opportunity in the shelter on top of Ringkollen (#StandStill 094) on a fantastic late-winter day.

Finding new spaces will obviously be more complicated later in the project, so I have started listing possible good spots. I am also happy to get suggestions for good places that I can explore.

Pre-processing and analysis

Early in the project, I wrote about my initial testing of the sensor data. I hadn’t worked in Python for a while when I got started, so the first day’s Jupyter Notebook shows my somewhat rusty programming skills. Fortunately, things were calm in January before the semester started, so I managed to spend a little extra time on code development. That is another nice thing about doing a project every day. Spending a few extra minutes on bug-fixing and new developments each day helps a lot.

During the winter break, I also had a little extra time and found that the current notebook (051) was becoming impractical to work with. So from day 52, I split the notebook into one for pre-processing the data (processed) and one for the analysis (cooked). The plan was (and still is) to develop these further. Unfortunately, it has been too busy these last weeks to do more than the bare minimum, so further development is on hold. Fortunately, the notebooks are in good enough shape to give me clean data and some preliminary analyses I can post on Mastodon.

On using Mastodon

Talking about Mastodon, this is the platform I have chosen as my communication channel for the project, posting under #StillStanding. Last year, I started my #SoundActions project on Twitter, but given the developments following Musk’s take-over, I decided to abandon the platform in November. One downside is that I have much fewer followers on Mastodon (for now, hopefully), so the project’s outreach is a magnitude smaller than it could have been on Twitter (if people had been staying). That is not a big problem; even though I post daily, this project will live on. It doesn’t matter whether people see it today or tomorrow; it is fuelling projects that will run for several years so that people will discover it eventually. Most importantly, using and supporting an open-source and community-driven platform feels good.

Privacy

I intend to make all files freely available, according to my Open Research advocacy. However, there are several reasons why that will only work out partially.

First, I stand still in private rooms that I (or the owners) don’t want to expose publicly. I want to avoid exploiting the hospitality of friends and colleagues, letting me use their homes and offices for my project. However, the project is not based on sharing 360-degree photos of every room I am in. There are multiple other ways of sharing information about the environments. Videograms contain relevant color information, and various audio visualizations show the audio. And the extracted quantitative data can be shared and used without any problems.

Second, even though I, for the most part, have been trying to stand still in rooms without people, there are occasions when people have “walked in” on me while standing there. Sometimes this has led me to cancel the recording; other times, the people passed, and I decided to continue. In any case, this project is not about people but about spaces, so I will not share any person-identifiable information (captured on video, audio, or both) in the project.

Those two concerns are minor, though; most recordings are okay to share, although the extracted features and the totality are more interesting to others than every single recording. The challenge up until now is that I have been trying to figure out how to share the data. I am leaning towards setting up an OSF repository but will still need to figure out how to organize it: by day, by media type, or by something else. It will probably have to wait until things calm down during summer to explore the best way to do this.

Equipment

I had done some initial testing, but I was unsure of how my technical setup (described in my first post about the project) would work in real-life usage. Things have generally worked well, although I have had to do several modifications during the project.

I started with a small and lightweight camera stand. It was perfect on paper, but, unfortunately, the head mount broke after only a couple of weeks; the camera and microphone combo leaning out on the side was too much for the construction. I thought about getting a new one but remembered an old stand I had lying around that I hadn’t used for anything else. It is small and well-constructed, although much heavier than the broke one. After having used it for a while, I have realized it is a vintage collector’s item, a Bilora Biloret Model 2017 Telescoping Travel Tripod. It turns out that a tripod from the 1950s is as small and much more sturdy than today’s equipment.

Another thing I figured out after a couple of weeks was that the Zoom H3-VR does not have rechargeable batteries. I am so used to everything being rechargeable that I didn’t think about it before; one day, the device shut off in the middle of a session. After that, I changed the batteries occasionally, but the battery indicator did not work well (it died on me even when it was supposed to be half-full). Fortunately, it can run with USB power, so the solution has been to add a battery pack to my setup. I bought a battery pack with two USB outputs to run the Zoom recorder and GoPro in parallel. Unfortunately, the GoPro cannot run from USB power, but at least it can charge when not recording. I need to charge the battery pack occasionally, though, but now that is part of my protocol.

Third, I have struggled with the door hatch to reach the GoPro’s USB-C connector. Initially, I relied on the wireless transfer of files from the GoPro camera. However, this has been time-consuming at best and failed many days. So I have reverted to a cable-based file transfer process. I removed the door to the battery pack to avoid all the trouble with the fiddly hatch. Then I can connect directly to the USB-C port on the camera without any problem. Of course, this means that the camera is not water-resistant, but that is fine for this project. Slightly more annoying is that the GoPro captures the cable sticking out on the side in the 360-degree view, but this is subordinate to the convenience of the faster file transfer.

Another significant change was that I decided to upgrade my Samsung Galaxy Ultra S21 to the newest S23 model. I am using my mobile phone for photography and quick video recordings, and upgrading my mobile phone was a better overall purchase than getting a separate camera that, in practice, wouldn’t travel with me every day. I have yet to study the sensors on the two phones systematically, but there shouldn’t be a big difference.

265 days to go

The first 100 days went easier than I thought. There have been some challenges, and I have learned a lot. Most importantly, I have collected a lot of data and taken a lot of notes about the experience of standing still and the rooms I have explored. I am looking forward to the next 265 days and analyzing all the data in more detail.