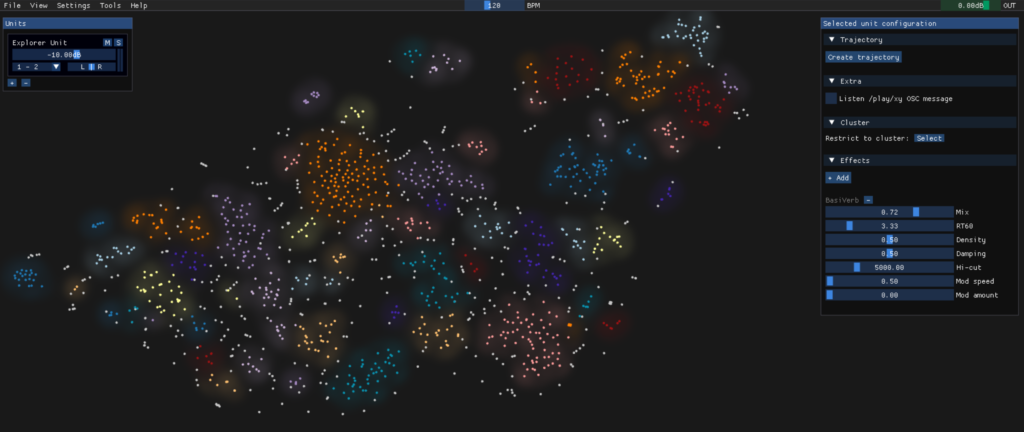

I have recently played with AudioStellar, a great tool for “sound object”-based exploration and musicking. It reminds me of CataRT, a great tool for concatenative synthesis. I used CataRT quite a lot previously, for example, in the piece Transformation. However, after I switched to Ubuntu and PD instead of OSX and Max, CataRT was no longer an option. So I got very excited when I discovered AudioStellar some weeks ago. It is lightweight and cross-platform and has some novel features that I would like to explore more in the coming weeks.

Samples and sound objects

In today’s post, I will describe how to prepare short audio files to load into AudioStellar. The software is based on loading a collection of “samples”. I always find the term “sample” to be confusing. In digital signal processing terms, a sample is literally one sample, a number describing the signal’s amplitude in that specific moment in time. However, in music production, a “sample” is used to describe a fairly short sound file, often in the range of 0.5 to 5 seconds. This is what in the tradition of the composer-researcher Pierre Schaeffer would be called a sound object. So I prefer to use that term to refer to coherent, short snippets of sound.

AudioStellar relies on loading short sound files. They suggest that for the best experience, one should load files that are shorter than 3 seconds. I have some folders with such short sound files, but I have many more folders with longer recordings that contain multiple sound objects in one file. The beauty of CataRT was that it would analyse such long files and identify all the sound objects within the files. That is not possible in AudioStellar (yet, I hope). So I have to chop up the files myself. This can be done manually, of course, and I am sure some expensive software also does the job. But this was a good excuse to dive into SoX (Sound eXchange).

SoX for sound file processing

SoX is branded as “the Swiss Army knife of audio manipulation”. I have tried it a couple of times, but I usually rely on FFmpeg for basic conversion tasks. FFmpeg is mainly targeted at video applications, but it handles many audio-related tasks well. Converting from .AIFF to .WAV or compressing to .MP3 or .AAC can easily be handled in FFmpeg. There are even some basic audio visualization tools available in FFmpeg.

However, for some more specialized audio jobs, SoX come in handy. I find that the man pages are not very intuitive. There are also relatively few examples of its usage online, at least compared to the numerous FFmpeg examples. Then I was happy to find the nice blog of Mads Kjelgaard, who has written a short set of SoX tutorials. And it was the tutorial on how to remove silence from sound files that caught my attention.

Splitting sound files based on silence

The task is to chop up long sound files containing multiple sound objects. The description of SoX’s silence function is somewhat cryptic. In addition to the above mentioned blog post, I also came across another blog post with some more examples of how the SoX silence function works. And lo and behold, one of the example scripts managed to very nicely chop up one of my long sound files of bird sounds:

sox birds_in.aif birds_out.wav silence 1 0.1 1% 1 0.1 1% : newfile : restart

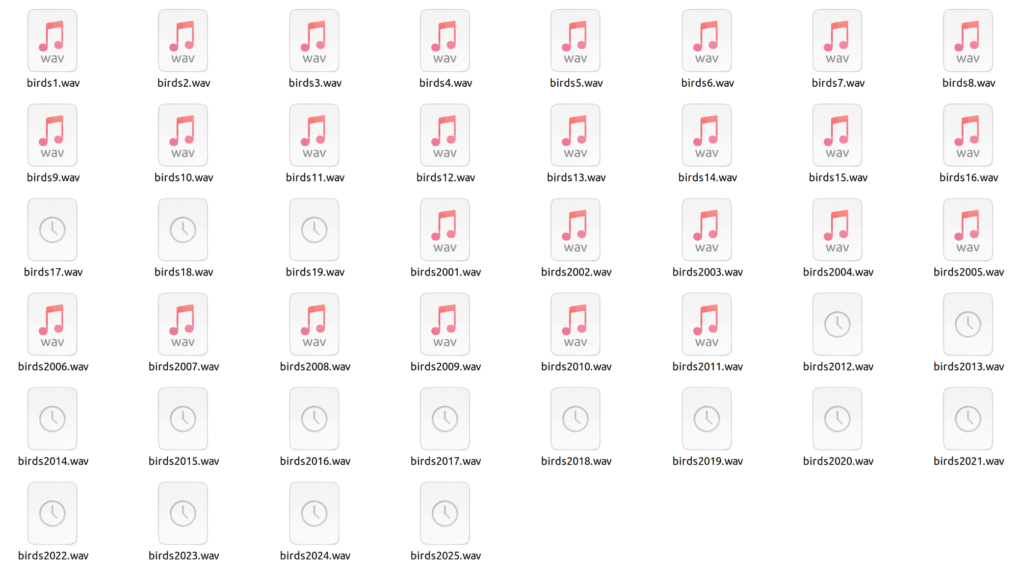

The result is a folder of short sound files, each containing a sound object. Note that I started with an .AIFF file but converted it to .WAV along the way since that is the preferred format of AudioStellar.

To scale this up a bit, I made a small script that will do the same thing on a folder of files:

#!/bin/bash

for i in *.aif;

do

name=`echo $i | cut -d'.' -f1`;

sox "$i" "${name}.wav" silence 1 0.1 1% 1 0.1 1% : newfile : restart

done

And this managed to chop up 20 long sound files into approximately 2000 individual sound files.

There were some very short sound files and some very long. I could have tweaked the script a little to remove these. However, it was quicker to sort the files by file size and delete the smallest and largest files. That left me with around 1500 sound files to load into AudioStellar. More on that exploration later.

All in all, I was happy to (re)discover SoX and will explore it more in the future. I was happy to see that the above settings worked well for sound recordings with clear silence parts. Some initial testing of more complex sound recordings were not equally successful. So understanding more about how to tweak the settings will be important for future usage.