Citizen Science is on everyone’s lips these days, at least on the lips of people working in research administration, funding agencies and in institutional leadership. As a member of the EUA Expert Group on Open Science/Science 2.0, I am also involved in ongoing discussions on the topic.

Yesterday, I took part in the workshop Citizen Science in an institutional context organized by EUA and OpenAire. A recording of my talk is available here:

Video is good for many things, but textual information may be easier to search for and skim through, so in this blog post, I will summarize some of the points from my talk.

As always, I started by briefly explaining my reasoning for talking about Open Research instead of Open Science. This is particularly important for people working within the arts and humanities, for whom “science” may not be the best term.

Defining Citizen Science

There are lots of definitions of citizen science, such as this one:

Citizen science […] is scientific research conducted, in whole or in part, by amateur (or nonprofessional) scientists.

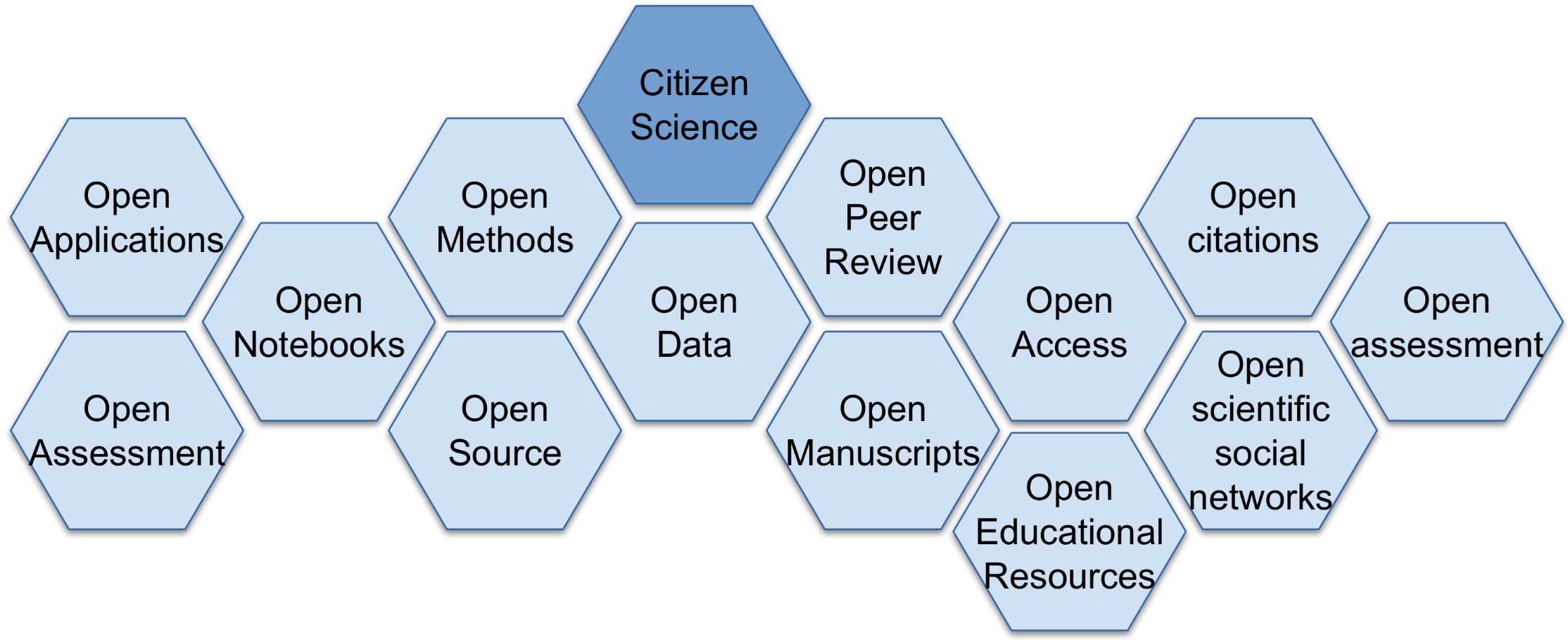

That is fine on a general level, but it is more unclear what it means in practice. In my experience, many people think of citizen science as primarily involving citizens in the data collection. Then citizen science is just one building block in the (open) research ecosystem:

Another, more open, definition of citizen science, focuses on the inclusion of citizens in all parts of the research process. This is the approach that I think is most interesting, and is the one I am focusing on.

Opportunities of Citizen Science

I have never thought of myself as a “citizen science researcher”. Some people build all their research on such an approach. For me, it has more been an add-on to other research activities. Still, I have done several citizen science-like projects over the years. In the talk, I presented two of these briefly: Hjernelæring and MusicLab. I will present these briefly in the following.

Case 1: Hjernelæring

The first case is my collaboration with Hjernelæring, a Norwegian company producing educational material for schools. I was challenged to create an exercise that could be used in classrooms, which could also be used to collect research data. My main research project at the moment (MICRO) is focusing on music-related micromotion, so it was natural to build an exercise around this. We have done several studies in the lab over the years, including the Norwegian Championship of Standstill. The latter has been an efficient way of attracting many participants to the study. We also try to give something back. All participants get a chance to download plots of their own micromotion, and we make the data available in the Oslo Standstill Database. So they are free to use and analyze the data if they wish.

Since we couldn’t rely on any particular technology in the classrooms, I ended up making an exercise where the kids would stand still with and without music, and then draw their experiences on a piece of paper. The teacher would then scan these drawings and send to me for analysis. I think this is a nice example of how to get involved with schools. It is research dissemination, because the kids learn about the research we are doing, why we do it, and what can come out of it. And it is data collection, since the teachers provide us with research data.

Case 2: MusicLab

The second case I presented was on MusicLab. This is an innovation project at the University of Oslo, where we at RITMO collaborate with the Science Library in exploring an extreme version of Open Research. Each MusicLab event is organized around a concert. The idea is to collect various types of data (motion capture, physiology, audio, video, etc.) of both performers and audience members that can be used in studying the event. There is usually also a workshop on a topic related to the concert, a panel discussion, and a data jockeying session in which some of the data is analyzed on the fly. As such, we try to open the entire research process to the public, and also include everyone in the data collection and analysis.

Challenges of Citizen Science

The last part of the presentation was devoted to presenting some of the challenges of Citizen Science. These were particularly focused on institutional challenges. There are, obviously, also many research challenges. Still, at the moment, I think it is important to help institutions to develop policies and tools for helping researchers to run Citizen Science projects.

My list of challenges include the need for (more):

- technical infrastructure for data collection, handling, storage, and archiving. Many institutions have built up internal systems for data flows, but it is usually difficult to share data openly. I also see that IT departments are usually involved in handling storage solutions, while libraries are involved in archiving. This creates an unfortunate gap between the two (storage and archiving).

- channels for connecting to citizens. Working with an external partner is usually a good strategy for connecting with citizens. Still, it also means that the researchers (and institutions) have to rely on a third party in communication with citizens. Some universities have built up their own Citizen Science centres, which may help with facilitating communication.

- legal support (privacy+copyright). All the “normal” challenges of GDPR, copyright, etc., become even more difficult when involving citizens at all stages of the research process. Clearly, there is a need for more support to solve all the legal issues involved.

- data management support. It is both a skill and a craft to collect data, handle data, equip data with metadata, store it, and archive it properly. Researchers need to learn all of these to some extent, but we also need more professional data managers to help at all stages. I think libraries’ future will largely be connected to the data management of various kinds.

- strategies for avoiding bias and pressure from citizens. One of the big criticisms/scepticisms of Citizen Science is that it may lead to all sorts of unfortunate effects. Research is under pressure many places, and by involving more people in the research process, this may also lead to several challenges. I believe that more openness is the answer to this problem. Transparency at all levels will help expose whatever goes on in the data collection and analysis phase. This may mitigate potential challenges arising from people trying to push the research in one way or another. This, of course, requires the development of solid infrastructures, proper metadata, persistent IDs, version control, etc.

- incentives and rewards for researchers (and institutions). Citizen Science is still new to many. As for anything else, if we want to make a change, it is necessary to support people interested in trying things out.

Conclusion

In sum, I believe there is a huge potential in citizen science. After thinking about it for a while, I think that more focus on Citizen Science is a natural extension of current Open Science initiatives. For that to happen, however, we need to solve all of the above. A good starting point is to develop policies from a top-down perspective. Equally important is to give researchers time (and some money) to set up pilot projects to try things out. After all, there will be no Citizen Science, if there are no researchers to initiate it in the first place.