I am presenting at the Norwegian Forskerutdanningskonferansen on Monday, which is a venue for people involved in research education. I have been challenged to talk about why open research is better research. In the spirit of openness, this blog post is an attempt to shape my argument. It can be read as an open notebook for what I am going to say.

Open Research vs Open Science

My first point in any talk about open research is to explain why I think “open research” is better than “open science”. Please take a look at a previous blog post for details. The short story is that “open research” feels more inclusive for people from the arts and humanities, who may not identify as “scientists”.

Why not?

I find it strange that in 2020 it is necessary to explain why we believe open research is a good idea. Instead, I would rather suggest that others explain why they do not support the principles of open research. Or, put differently, “why is closed research better research”?

One of the main points of doing research is to learn more and expand our shared knowledge about the world. This is not possible if we do not share the very same knowledge. Sharing has also been a core principle of research/science for centuries. After all, publications are a way of sharing.

The problem is that a lot of today’s publishing is a relic from a post-digital era, and does not take into account all the possibilities afforded by new technologies. The idea of “Science 2.0” is to utilize the potentials of web-based tools in research. Furthermore, this does not only relate to the final publications. A complete open research paradigm involves openness at all levels.

What is Open Research?

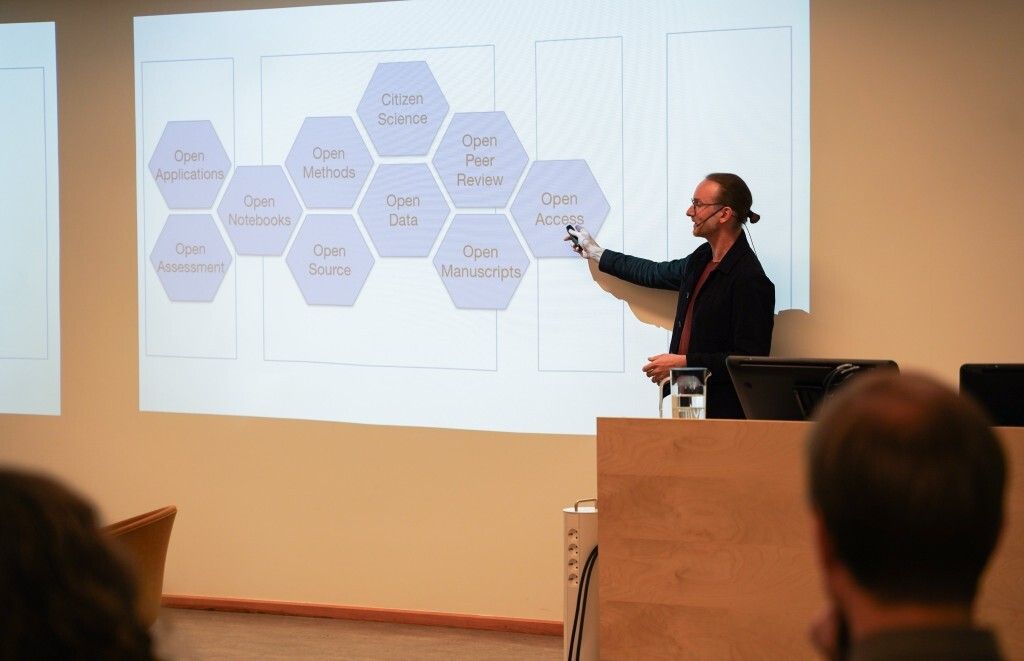

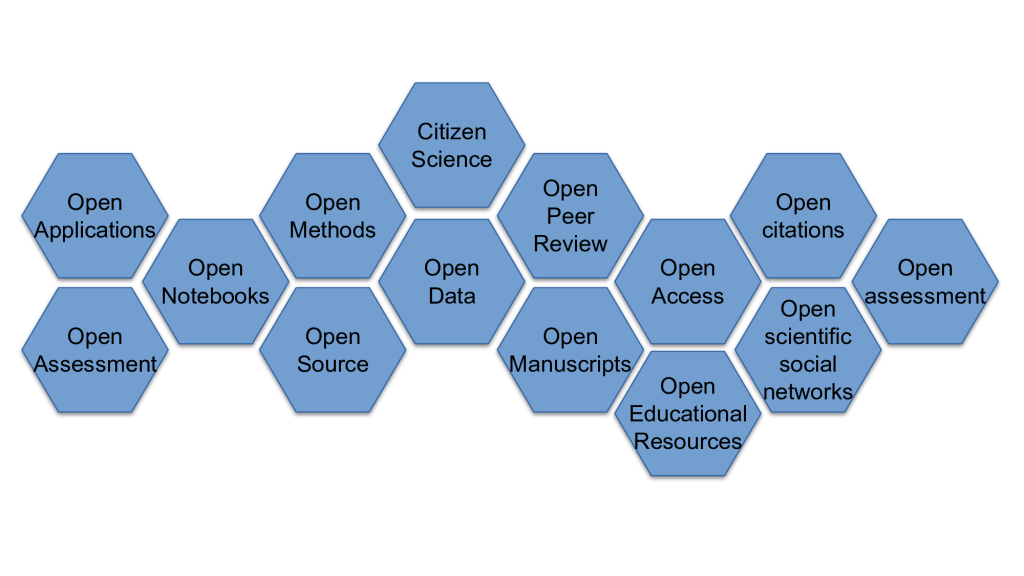

There are many definitions of open research, and I will not attempt to come up with the ultimate purpose here. Instead, I will point to (some) of the building blocks in an open research paradigm:

One can always argue about the naming of these, and what they include. The most important is to show that all parts of the research process could, in fact, be open.

How does open research help making better research?

To answer the original question, let me try to come up with one statement for each of the blocks mentioned in the figure above:

- Open Applications: Funding applications are mainly closed today. But why couldn’t all applications be made publicly available? These would lead to better and more transparent processes, and the applications themselves could be seen as something others can build on. For people to avoid stealing ideas, such public applications would, of course, need to have tracking of applicant IDs, version-controlled IDs on the text, and universal time codes. That way, nobody would be able to claim that they came up with the idea first. One example is how DIKU decided to make all applications and assessments for the call for Centres of Excellence in Education open.

- Open Assessment: If also, the assessment of research applications were open, this would increase the transparency of who gets funding, and why. The feedback from reviewers would also be openly available for everyone to see and learn how to develop better applications in the future.

- Open Notebooks: Jumping to when the actual research starts, one could also argue for opening up the entire research process itself. This could involve the use of open notebooks explaining how the research develops. It would also be a way of tracking the steps taken to conduct the research, for example, getting ethics permissions. This could be done on web pages, blogs, or with more computational tools like Jupyter Notebook.

- Open Methods: During review processes of publications, one of the trickiest parts is to understand how the research was conducted. Then it is crucial that the methods are described clearly and openly. Solutions like the Open Science Framework try to make a complete solution for making material available.

- Open Source: An increasing amount of methods are computer-based. Sharing the source code of developed software is one approach to opening the methods used in research. It is also of great value for other researchers to build on. Some of the most popular platforms are GitHub and Gitlab.

- Citizen Science: This is a big topic, but here I would say that it could be a way of opening for contributions by non-researchers in the process. This could be anything from participating in research designs to help with collecting data.

- Open Data: Sharing the data is necessary so that reviewers can do their job in assessing whether the research results are sane. It is quite remarkable that most papers are still accepted without the reviewers having had access to the data and analysis methods that were used to reach the conclusions. Of course, open data are also of value for other researchers that re-analyze or perform new analysis on the data. In my experience, data are under-analyzed in general. There are numerous platforms available, both commercial (Figshare) and non-profit (Zenodo).

- Open Manuscripts: Many researchers have been sharing manuscripts with colleagues and getting feedback before submission. With today’s tools, it is possible to do this at scale, asking for feedback on the material even at the stage of manuscripts. There are numerous new tools here, including Authorea and PubPub.

- Open Peer Review: A traditional review process consists of feedback from 2-3 peers. With an open peer review system, many more peers (and others) could comment on the manuscript, thereby also improving the final quality of the paper. One interesting system here is OpenReview.

- Open Access: Free access to the final publication is what most people have focused on. This is one crucial building block in the ecosystem, and much (positive) has happened in the last few years. However, we are still far from having universal open access. This is a significant bottleneck in the sharing of new knowledge. Fortunately, the political pressure from cOAlition S and others help in making a change.

- Open Educational Resources: Academic publications are not for everyone to digest. Therefore, it is also imperative that we create material that can be used by students. This is particularly important to support people’s life-long learning. The popularity of MOOCs on platforms such as EdX, FutureLearn, and Coursera, has shown that there is a large market for this. Many of these are closed, however, which prevents full distribution.

- Open Citations: Whether you work is cited by peers or not is often critical for many people’s careers. It has become a big business to create citation counts and various types of indexes (the h-index being the most common). The chase for citations has several opposing sides, including self-citations, and dubious pushing for citations to reviewers’ material. Therefore, we need to push for more openness, also when it comes to citations and citation counts.

- Open Scientific Social Networks: The way people connect is vital in the world of research (as elsewhere). Opening the networks is crucial, particularly for minority researchers, to get access. Diversity will generally always lead to better and more balanced results.

- Open Assessment: The last block takes us back to the first one. This relates to the assessment of research and researchers and is a topic I have written about before. I also helped organize the 2020 EUA Workshop on Academic Career Assessment in the Transition to Open Science, which has a lot of excellent material online.

Conclusion

As my quick run-through of the different parts of the building blocks has shown, it is possible to open the entire research process. Much experimentation is happening these days, and convergence is happening for some of the blocks. For example, the sharing of source code and data has come a long way in some communities. Some journals even refuse manuscripts without complete data sets and source code. Other parts have barely started. Open assessment may have come shortest, but things are moving also here.

My main argument for opening all parts of the process is that is “sharpening” the research process. You cannot be sloppy if you know that it will be exposed. I often hear people argue that it takes a lot of time to make everything openly available. That is also my experience. On the other hand, why should research be so fast. It is better to focus on quality than quantity. Open research fosters quality research.

One of the most common objections to opening the research process is that other people will steal your ideas, data, code, and so on. However, if everything is tagged correctly, time-stamped, and given unique IDs, it is not possible to steal anything. Everything will be traceable. And plagiarism algorithms will quickly sort out any problems.

The biggest challenge we are facing is that it is challenging to balance between the “old” and the “new” way of doing research. That is why policymakers and researchers need to work together with funders to help flip the model as quickly as possible.